Rethinking Military Intelligence

4th Generation Warfare:Doctrinal Adaptations to Asymmetric Enemy

Ww2int

GERMAN RADIO INTELLIGENCE

BY LIEUTENANT-GENERAL ALBERT PRAUN

Biographical Sketch of the Principal Author

Albert PRAUN was born 11 December 1894 in Bad Gastein, Austria. He entered the German Army in the 1st Bavarian Telegraph Battalion as an officer candidate in 1913 and served as battalion and division signal officer during World War I. He remained in the post-war Army and in 1939 was assigned to the Seventh Army on the Western Front as army signal officer. During World War II PRAUN served as regimental, brigade, and division commander, and also as army and army group signal officer in France and Russia. In 1944 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and simultaneously appointed Chief of Army and Armed Forces Signal Communications in which capacity he remained until the end of hostilities.

List of Other Contributors

(Last rank held and assignments relative to the present subject)

de Bary. Major, commander of radio intercept units.

Bode. Captain, intercept platoon leader: chief of the clearing center of Communication Intelligence West.

Gimmler. Major General, Chief Signal Officer under the Commander in Chief West and Chief of the Armed Forces Signal Communication Office. [Tr: Oberbefehlshaber, hereafter referred to as OB]

Gorzolla. Captain, liaison officer between the clearing center of communication intelligence and the Eastern Intelligence Branch.

Halder. Colonel, commander of intercept troops for an army group.

Henrici. Lieutenant colonel, General Staff, chief signal officer for C3 West.

Hepp. Colonel, General Staff, Deputy Chief of Army Signal Communication.

Karn. Colonel, army signal officer.

Kopp. Colonel, senior communication intelligence officer for OB West.

de Leliwa. Lieutenant colonel, chief of evaluation for OB West.

Marquardt. Major, liaison officer between the clearing center of communication intelligence and the Western Intelligence Branch, Army General Staff.

Mettig. Major, chief of the cryptoanalysis section of the main intercept station.

Muegge. Colonel, communication intelligence officer for an army group.

Foppe. Major, signal battalion commander.

Randewig. Colonel, commander of intercept units with various Army groups.

Seemueller. Lieutenant colonel, communication intelligence officer for several army groups.

Stang. Captain, radio company commander, armored divisions.

Chapter One. Introduction

Because of the difficulties encountered in this highly specialized field the topic required treatment by an expert of recognized standing. Since such an expert was not available among the men in the German Control Group working under the supervision of the Historical Division, SUCOM, the writing of the over-all report was assigned to General Praun. By virtue of the knowledge acquired by him in his military career, and especially during the tenure of his final position, General Praun has a thorough grasp of German radio intelligence. Moreover, as a result of his acquaintance with German signal service personnel, he was able to obtain the co-operation of the foremost experts in this field.

The German Control Group has exerted a guiding influence on the study by issuing oral and written instructions concerning the manner in which the subject was to be handled. Above all, it reserved to itself the right of final decision in the selection of the contributors and also retained control over the individual reports themselves.

With regard to the treatment of the topic assigned, General Praun, with the approval of the Control Group, decided to make his report in the form of a study in military history. Since no comprehensive records were available, he assembled the basic material for the various theaters of war and the most important campaigns by enlisting the aid of signal officers who had served in radio intelligence in the respective theaters. This material was supplemented by reports from officers who had hold important positions as experts in various branches of radio intelligence in the Array High Command and the Armed Forces (Wehrmacht) High Command [Tr: Oberkommando des Heeres, hereafter referred to as OKH; Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, hereafter referred to as OKW]. From the successes and failures of German radio intelligence General Praun has established criteria for appraising the enemy radio services. He is thus able to present an actual picture of the Allied radio services as seen from the German side during the war.

An attempt was made to include an account of all major American and British military operations against the German Army, and an appraisal of their use of radio communication. The material on Russia was treated in a different manner. Because of the vastness of the Russian theater of war and because the same observations concerning radio communication were made along the entire front, the results obtained by communication intelligence units serving with only one army group have been described. They are supplemented by accounts from other sectors of the Russian front.

In keeping with German practice since 1942, the term "communication intelligence" (Nachrichtenaufklaerung) has been used when units thus designated were assigned to observe enemy radio and wire communication, (The latter activity lost almost all importance as compared with the former.) Where the observation of enemy radio communication alone is discussed, the term "radio intelligence" (Funkaufklaerung) is used or — as was customary until 1942 — the term "intercept service" (Horchdienst).

Chapter Two. The Significance of Electronic Warfare

Toward the end of World War II about 12,000 signal troops of the German Army were engaged in intercepting the radio traffic of an increasingly powerful enemy. With the decline of the information gained by intelligence through aerial observation, prisoner of war interrogations, and reports from enemy agents, communication intelligence became increasingly important. In spite of the constant attempts of all enemies to improve radio communication and increase its security, German signal troops were able again and again to gain access to the information transmitted by this medium.

Thanks to communication intelligence, German commanders were better informed about the enemy and his intentions than in any previous war. This was one of the factors which gave the German command in the various campaigns of World War II a hitherto unattained degree of security. The fact that, during the final years of the war when the German Army Command was leading exhausted and decimated troops without reserves, it was able to offer less and less resistance to clearly recognized measures and intentions of the Allies, and that Hitler was unwilling to acknowledge the true situation on all fronts and the growing enemy superiority as reported in accurate detail by communication intelligence, is one of the deep tragedies of the German soldier.

Since wireless telegraphy and later wireless telephony were first used for military communication, there was no pause in the eventful contest between this important instrument of the German command (and subsequently also of troop units) on the one hand, and the corresponding facilities of the enemy on the other, as each side tried to profit from his knowledge of the other's communications as he prepared his countermeasures.

Following the first amazing successes scored by radio intelligence of a high-level nature in World War I, the quantity of information obtained, including that pertaining to tactical operations, increased so enormously with the amount of radio apparatus used by all the belligerent powers that large-sized "organizations had to be established for handling them.

The active radio services in all armies tried to insure the secrecy of their messages by technical improvements, by speed in operation, by chancing their procedure, by mere complicated cipher systems, by accuracy in making calls and replies and in transmitting other signals, all of which constituted "radio discipline." However, in opposition to these developments the enemy also improved his passive radio service, his technical equipment, his methods of receiving, direction finding, and cryptanalysis. The important part played in this contest by the proficiency of the technical personnel involved will be described later.

At the same time that this form of electronic warfare was being waged in World War II, there was another aspect which also gained steadily in importance, namely, the more technical high frequency war between opposing radar systems. This consisted of the use of microwaves for the location and recognition of enemy units in the air and on the sea, and the adoption of defensive measures against them, especially in air and submarine warfare.

For the sake of completeness there should also be mentioned the third aspect of electronic warfare, the "radio broadcasters' war* in which propaganda exports tried to influence any as well as other countries, by means of foreign language broadcasts over increasingly powerful transmitters.

All three aspects of this modern "cold war of the air waves" were carried on constantly even when the puns were silent. This study will be restricted to a description of the first aspect of electronic warfare.

Chapter Three. German Radio Intelligence Operations (1936 - 45)

In addition to the intelligence gained from interesting the routine radio traffic in peacetime and the occasional activity during maneuvers, the political and military events which preceded the outbreak of World War II offered abundant material because of the increased traffic between the nations concerned, the larger number of messages, and the refinements and deficiencies in communication systems which had hitherto not come to light. During this period the German communication intelligence organization and the specialists employed in it gathered a wealth of information. Without any lengthy experimentation they were later on able to solve the increasing number of new problems which resulted from the extension of the war.

I. Spanish Civil War (1936 - 39)

In the Spanish Civil War the supporting powers on both sides had opportunities to become acquainted with the radio systems, radio equipment, and cryptographic methods of their opponents. The German intercept company assisting Franco obtained much information on these subjects. Because of its successes this company was always assigned to the focus of the military operations.

II. Czechoslovakia (1938)

For a long time the entire radio net traffic of Czechoslovakia was easy to intercept and evaluate. It was observed by fixed listening posts and intercept companies in Silesia and Bavaria, subsequently also by stations in Austria. Toward the end of May 1938 one of the key radio stations in Prague, probably that of the War Ministry, suddenly transmitted a brief, unusual message which, in view of the existing political tension, was believed to be an order for mobilization. This message was immediately followed by changes in the radio traffic characterized by the use of new frequencies and call signs, and by the regrouping of radio nets which had been prepared for the event of mobilization. The result was that the intercept company then on duty was able within two and a half hours to report the mobilization of Czechoslovakia. During the next few days very primitive, simple radio nets appeared along the border and then disappeared again when the tension was relaxed, where-upon the entire radio net reassigned its original characteristics. Radio Intelligence was able to report that the mobilization order had presumably been revoked.

In the middle of September of the same year something incredible happened. The Czechs repeated what they had done in the spring. Again they announced the mobilization order by radio and within a few minutes the message was forwarded to Berlin. Again the same primitive radio nets appeared along the border with almost the same call signs and on the same frequencies.

This intercept operation was a practical object lesson, while the radio Service of the Czechs was a classical example of how not to carry en radio operations.

III. Polish Campaign

Polish radio communications were also well known, as the result of long observation, and were intercepted from points in Silesia and East Prussia. During the period of tension in the summer of 1939 the Germans observed not only the regular traffic but also a great number of field messages which increased daily and was far out of proportion to the known organization and radio equipment possessed by the Polish Army. As was soon conjectured and then later confirmed during hostilities, the purpose of this was to camouflage Polish radio communications by using three call signs and three frequencies for each station. Intelligence officers engaged in the evaluation of traffic and D/F data were unable to derive any detailed tactical picture from the intercepted messages. Nevertheless, the intercept service confirmed that the Polish assembly areas were located where the German General Staff had assumed them to be. It can no longer be determined whether the Poles employed these artifices for purposes of deception, as well as camouflage, in order to simulate stronger forces than they actually possessed. In any case, the failure to observe radio silence in the assembly areas was a grave mistake.

In 1939 the mobile facilities of the German intercept service were still inadequate. The intercept companies were insufficiently motorized and there was no close co-operation between them and the army group and army headquarters. The Polish radio communication system failed after the second day of the campaign, when it attempted to take the place of the wire lines destroyed by German air attacks. Probably as a result of the intercept successes they had scored in 1920, the Poles had restricted their peacetime radio activity to a minimum. As soon as they tried to carry out deception without previous practice in mobile operations, their radio communication collapsed completely. It was unable to keep pace with the rapid movements of the retreat, and moreover, the Poles were seized by the same type of radio panic that will be discussed later in the section of Allied invasion in Normandy. Clear-text messages revealed that many stations no longer dared to transmit at all, fearing they would he located by our direction finders and attacked from the air.

The Polish Army was thus unable to employ its radio communication for command purposes. Its leading source of information regarding the situation at the front were the OKW communiques, which, at that time, accurately reported every detail with typical German thoroughness. This mistake was corrected in the German campaign in the West in 1940. Intercept results were insignificant, since the Poles transmitted hardly any radio messages. The messages of some individual units were intercepted until there disbanded at the Galician-Romanian border. It was possible to solve several simple field ciphers even without trained cryptanalysts. Another mistake made by the Poles was the transmission of messages in the clear by the station of the Military Railway Transportation Office in Warsaw, which openly announced the time, route, and contents of railway shipments. These trains were successfully attacked by the Luftwaffe, which was further aided by other plain-text Polish traffic.

IV. USSR (1939 - 40)

After the conclusion of the Polish Campaign, the intercept company stationed in Galicia in the Sanok - Jaroslav - Sandomir area was charged with intercepting the traffic emanating from Russian units occupying eastern Poland. Thanks to their previous experience against Czechoslovakia and Poland, personnel of this company were so well trained that they rapidly became skilled in this new type of work. This company was not engaged in cryptanalysis. Solely on the basis of D/F reports and an evaluation of the procedure and traffic characteristics of the heavy traffic handled by the numerous stations, the Germans were able to deduce that a large number of troop units were in the area, but were at first incapable of ascertaining their organizational structure. All that could be determined was whether those units belonged to the army, the air force or to the NKVD [Tr: Comissariat of Internal Affairs, see TM 30-430, 1-26], whose radio operations were distinguished by a different technique from that used by the regular armed forces. For several months during the period of re-groupment everything was in a state of flux. The Soviet radio traffic was, however, well organized and efficiently handled.

Then the company intercepted messages from areas which were not actually assigned to it. When Soviet troops occupied the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and when they Subsequently attacked Finland, their short-wave transmissions from these areas were surprisingly well received in southern Galicia — even better than in areas further north. This was the discovery of great technical importance for the German intercept service. It could not have been arrived at by simple calculation since it resulted from physical conditions.

An abundance of messages, often in the clear, were received from the Baltic states and the Finnish theater of war, so that in the final stages of evaluation it was now possible to deduce the Soviet order of battle. In the case of units of division size and below their withdrawal from the Baltic States wan frequently ascertained on the basis of data including numbers, names of officers, and place names. Subsequently these elements turned up on the Finnish front in easily identified locations, from where they again disappeared after a while, only to reappear in the Baltic area or eastern Poland. Some vanished from observation altogether. From this fact it could be deduced that they had been transferred to the interior of the Soviet Union. Thus, the Germans could follow all movements of forces during the Russo-Finnish War simply by reading the intercept situation chart.

The radio communication of the Soviet Army in 1939 - 40 was efficient and secure under peacetime conditions, but in time of war, or under war-like conditions, it offered many weak spots to an enemy intercept service and was a source of excellent information for the German intelligence service.

V. German Campaign in the Balkans (I94I)

Since the results obtained from radio interception during the German campaign against Yugoslavia, Greece and the British Expeditionary Force are not of any special importance for an over-all appraisal of the subject, the campaign in the Balkans will be introduced at this point as one of the events preceding the beginning of major operations.

The German Army's organization for mobile warfare war still incomplete; results were jeopardized at first by the great distances between the intercept stations and the target areas, and later on by defective signal communication which delayed the work of evaluation. Intercept operations against the British will be described in detail in section VIII.

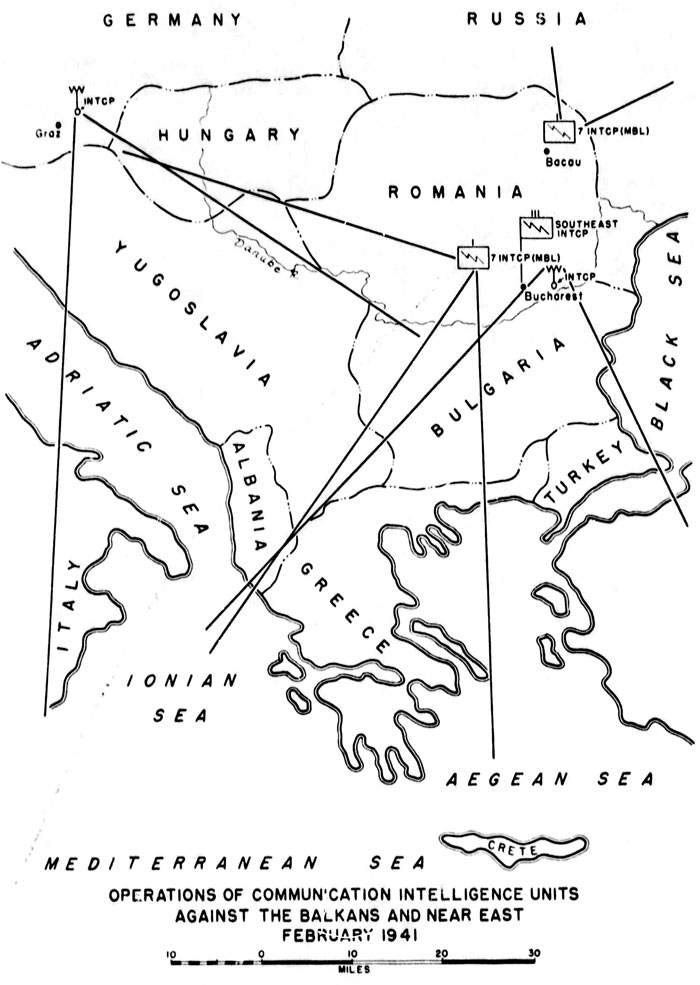

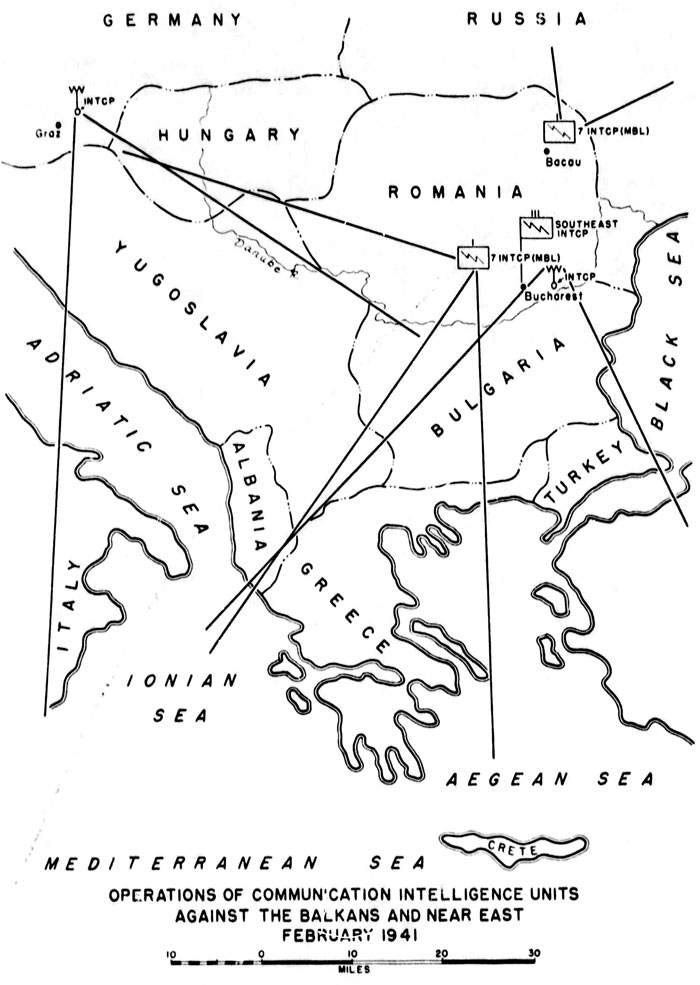

Chart 1. Operations of Communication Intelligence Units Against the Balkans and the Near East, February 1941

The Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast, whose headquarters is indicated in Chart 1 as being that of a regiment, was responsible to Field Marshal List, the Twelfth Army Commander. He was in charge of the two fixed intercept stations In Graz and Tulln (near Vienna) and two intercept companies. His sphere of action comprised the entire Balkan Peninsula, Turkey, and the British forces in Greece and the Middie East.

Until late 1940 radio interception against Greece and the Near East was carried out only as a secondary task and with inefficient resources by the Tulln station. The great distances, for instance 780 miles between Vienna and Athens and 1,440 miles between Vienna and Jerusalem, were a significant factor. (For purposes of comparison with intercept operations in the West it might be mentioned that the distance between Muenster and London is only 312 miles.) The value of the results was in inverse proportion to the distance involved.

In the beginning of 1941, when it was planned to enlarge the intercept service against Greece, especially after the landing of the British forces, the above-mentioned units, except for the Graz station, were transferred to Romania. In February 1941 the Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast and his evaluation center were stationed in Bucharest. From a location near this city the "Tulln station" covered Greece, giving its main attention to British communications emanating from there and the Middle East. One of the intercept companies also located in the vicinity of Bucharest observed Yugoslavia in addition to British radio traffic in Greece. The other intercept company in Bacau (150 miles northeast of Bucharest) had to carry out intercept operations against Soviet Russia and the Romanian police, whereas the Graz station, whose main attention was directed at Yugoslavia and Italy, intercepted traffic of the Romanian and Hungarian police. (See Chart 1).

Before the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans the Germans detected Greek army units in the northeastern corner of the country, Royal Air Force operations around Patras and between Patras and Athens, and British ground forces in Cyrenaica. They also intercepted messages from British border troops in Transjordan.

After the entry of German troops into Bulgaria the above-mentioned units (except the Graz station) were transferred to that country, and the intercept company in Bacau also covered Greece. The results were similar to those formerly obtained. It was not yet possible, however, to break the Greek ciphers because of an insufficient number of intercepted messages, and the German units had to be content with traffic analysis. On the other hand, it was possible to break the British field cipher in Palestine.

Following the attack upon Greece on 6 April brisk radio traffic was intercepted and evaluated. The disposition of the Greek forces in northern Greece was revealed and could be traced. West of the Vardar in the British Expeditionary Force sector, our intercept units detected three radio nets comprising fourteen stations, representing an armored unit northeast of Veria which was subsequently transferred to the area south of Vevi, a British division north of Katerini, and another division west of Demetrios. It was confirmed that these forces had remained for several days in the areas reported. On 8 April, the following British message in clear text was repeatedly heard: "DEV reporting from LIJA — Strumica fallen, prepare immediate return!"

In the Near East we followed the movement of a British regiment from Palestine to Egypt. The first indication of this was the message of a paymaster in the British military Government ordering a certain agency to be particularly careful to prevent the departing regiment from taking any filing cabinets along with it, since they were needed by the military government office. Thereafter, the recipient's movements could be clearly traced.

Radio intelligence against Yugoslavia produced an excellent picture of enemy positions. Three Armeegruppen [Tr: a weak improvised army under an army commander with an improvised army staff] and one corps from each were located near Nish, Ueskueb and Stip, and later one at Veles.

Very little radio traffic was heard in Turkey. By the middle of April German radio intelligence located Greek troop units between the Aliakmon River and the Albanian border, and also followed the witndrawal of a British armored unit from the vicinity of Vevi to the Kozani area, subsequently to Eleftochorion, and thence to Trikkala. The withdrawal of both British divisions (Anzac Corps) and, a few days later, further withdrawals to the area of Larisa were observed.

In the middle of April the Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast moved to the Salonika area with the "Tulln station," elements of the Graz station, and one intercept company. The other intercept company was released for service in Russia.

Greek radio traffic diminished rapidly and ended with the capitulation on 21 April. German intercept units continued to follow the traffic of the British Expeditionary Force until it disappeared from the air after the final embarkation in late April. The intercepting of British traffic from Crete and the Aegean islands was continued. During subsequent British operations in the Dodecanese Islands, for instance the occupation of Rhodes, the enemy often transmitted important situation reports in the clear.

VI. Norway and Denmark (1940)

The mobile operation of an intercept platoon in the Norwegian Campaign in I940 suffered from all the defects inherent in inadequately prepared improvised operations. A few radio operators were picked from each of six different units in the West, but no translators or cryptanalysts. The equipment was also inadequate. Later on, there was no shipping space to move the platoon up. In time and close enough to the German operations staff and the enemy area which war to be covered, nor was the platoon given any data or instructions.

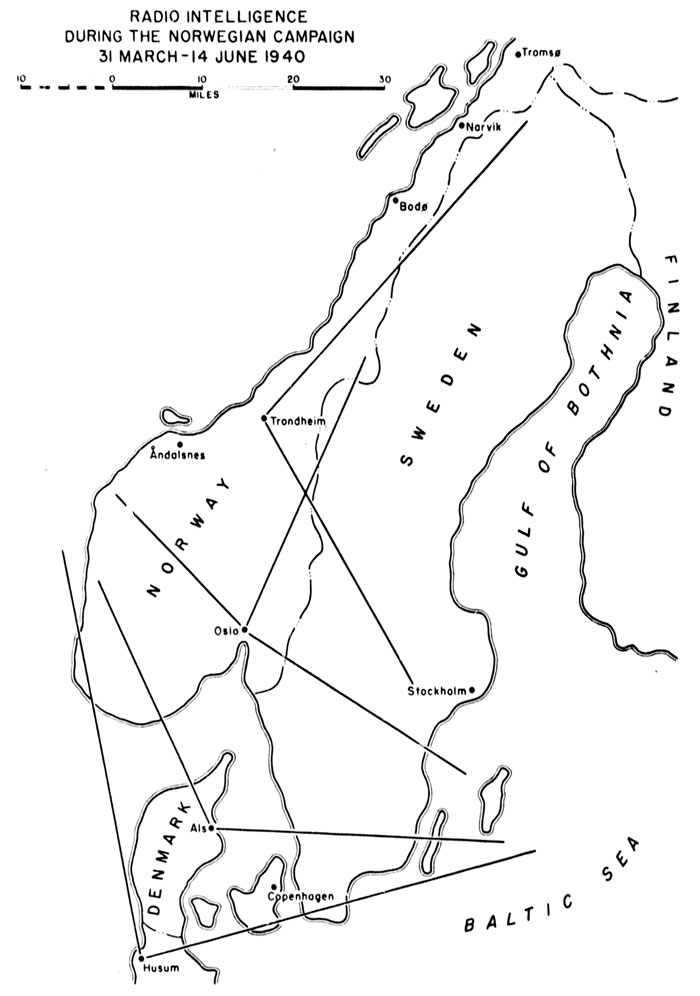

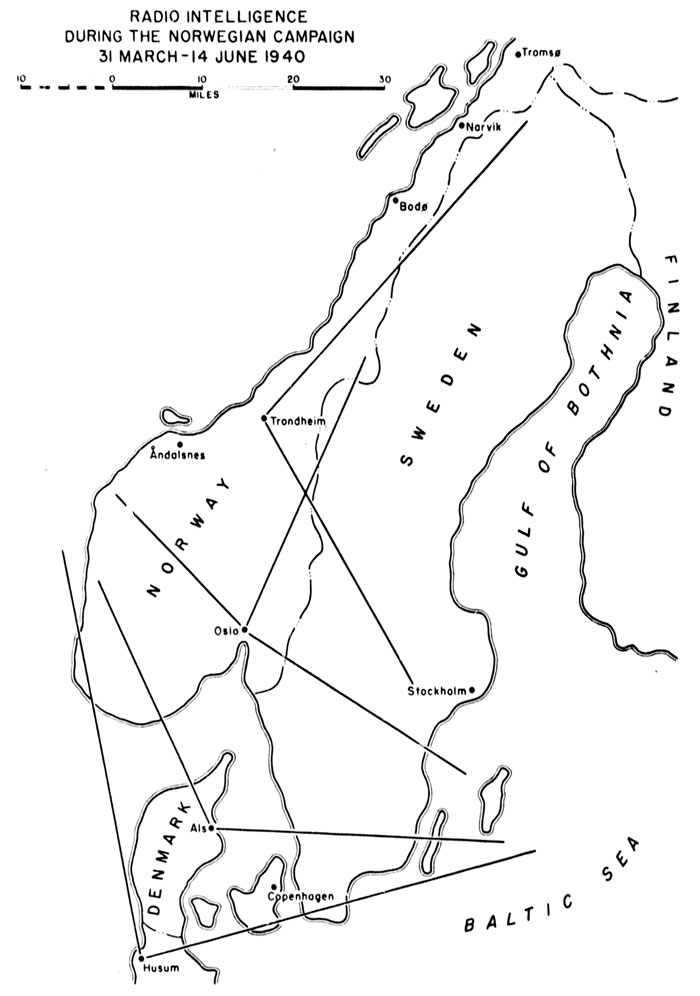

In its first operation, which was carried out with the assistance of the Husum Fixed Intercept Station, the platoon intercepted only coastal defense messages in clear text from Denmark concerning ship movements. No army radio traffic was heard. Even these messages ceased on 9 April. Because of the great distance only a few Norwegian coastal stations were heard. Up to 8 April this traffic was normal, but on the night of 8 - 9 April it increased to a point of wild confusion. Normal army radio traffic was observed in Sweden. After the platoon's first move to Als on the Kattegat, Norwegian Army messages were also intercepted, as well as traffic between Swedish and Norwegian radio stations. It was not until 24 April, that is, eleven days after the operations had commenced, that the intercept platoon was moved up to Oslo and thus employed in the vicinity of the German operations staff. (Chart 2)

Chart 2. Radio Intelligence During the Norwegian Campaign, 31 March - 14 June 1940

The Norwegian Army stations usually transmitted in the clear. Radio stations in central and southern Norway were intercepted, but few of the massages were of any tactical value.

Radio messages between Great Britain and Norway were more important. The admiralty station transmitted encrypted orders to the naval officers in command of Harstadt, Andalsnes, and Alesund. Although these messages could not be solved, they provided clues to the most important debarkation ports of the British Expeditionary Force. In particular, they confirmed the landings near Harstadt, which had hitherto been merely a matter of conjecture.

The Germans intercepted the field messages of the British units which were advancing from the Andalsnes area by way of Dombas - Otta - Hamar to Lillehammer in the direction of Oslo. They used code names for their call signs and signatures. The messages themselves could not be solved. However, since the code names ware learned after a short time from captured documents, the chain of command and composition of units were soon clearly recognized and the enemy's movements were followed.

Swedish radio stations were frequently heard transmitting to Norwegian stations. They handled mostly official and business messages. Norwegian radiograms were then often relayed from Sweden to Great Britain.

When, in the middle of May, a part of the German command staff was transferred to Trondheim the intercept platoon went along and found especially favorable receiving conditions near this city, which is approximately 1,500 feet above sea level. A large Norwegian radio net regularly transmitted air reconnaissance reports, information on the composition and commitment of the Norwegian 7th Division, and mobilization orders for the unoccupied part of Norway. They mentioned General Fleischer as commander in northern Norway.

Two radio stations continued to operate east of the island of Vega in the rear of the German 2d Mountain Division, which was advancing to relieve Narvik, until they were knocked out as the result of intercepts. The majority of the radio stations which were observed were in the Narvik area or north of it. The Alta ski battalion was often mentioned as being in action. Additional stations of other radio nets were identified in Kirkenes, Vardo, Harstadt, Tromse and Honningsvag, After the end of hostilities on 9 June all Norwegian radio traffic stopped within a few hours. Messages from British and French units were also picked up, as well as the traffic of the Polish mountain units. For the purpose of avoiding confusion with internal French traffic, a temporary teletype line to the commandor of the German intercept troops in France was set up, so that any sky waves from France could be recognized and timed out.

In order to furnish Kampfgruppe [Tr: a term loosely assigned to improvised combat units of various sizes, named usually after their commanders] Dietl in Narvik with radio inteligence of purely local importance without any loss of time, the intercept platoon was ordered to organize a short-range intelligence section, but as a result of the development of the situation this section never saw action. Instead, intercepts of interest to Kampfgruppe Dietl were forwarded to it through Sweden by telephone and teletype. During 7 and 8 June all non-Norwegian radio traffic stopped. In this way the withdrawal of the Allies from Narvik wan confirmed. This was also reported to Kampfgruppe Dietl.

The traffic between Great Britain and Norway, which had already been intercepted near Oslo, was now observed in larger volume from Trondheim. Most of the traffic was between Scotland (possibly Prestwick) and Bode or Tromse. The volume of messages was very large. The average word count was 200 letters. Every evening the Germans intercepted situation reports of the Norwegian High Command in Tromse, orders from the Admiralty in London, mine warnings, SOS calls, government radiograms to England and France, personal messages from King Haakon to King George of England and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and reports from the Reuter correspondents attached to Norwegian units.

On 25 May the radio station in Bode was destroyed by German bombers. Scotland called Bode for twelve hours in vain. Messages then transmitted by the Vadso Station were immediately intercepted. The Germans continued to intercept the traffic between Norway, Sweden and Great Britain.

Both the Trondheim station and the intercept platoon radioed a demand for surrender to the Norwegian High Command in Tromse. After its acceptance these radio channels were kept in operation until the middle of June when the platoon was disbanded and its personnel returned to their former units on the Western Front.

British radio traffic was, as usual, well disciplined and offered few opportunities to German radio intelligence. For this reason the intercept platoon endeavored to work on as broad a scale as possible, to intercept a large number of messages, and to probe for soft spots. Since it lacked special equipment and suitable personnel, the British ciphers could not be solved. Therefore, clear-text messages or code names and traffic analysis had to suffice as source material. The evaluation, therefore, was based chiefly on the procedural aspects of enemy radio operations.

Today it appears incomprehensible why the British seriously impaired the value of their well-disciplined radio organization and their excellent ciphers by transmitting call signs and signatures in the clear. Operating mistakes of this kind provided valuable information to the German intercept service, although it was poorly trained and insufficiently prepared. Subsequent experience on other battlefields showed that more extensive and intelligent efforts on the German side would have resulted in even more opportunities for breaking British ciphers.

British-Norwegian radio traffic was typical of the deficiencies which develop in a coalition with a weaker ally. It was carried on according to Norwegian standards and offered a wealth of information to German communication intelligence. The British and Norwegians were apparently unable to use a common cipher. On the other hand, the operating efficiency of their radio communication was high. The Norwegian personnel appeared to have been recruited from the ranks of professional radio operators.

At this point it should be repeated that the use of clear-text messages and code names should be avoided as a matter of principle. If code names were considered indispensable, they should have been frequently changed. A decisive transmission error prominent in traffic between the British Isles and Norway was the use of call signs in the clear as listed in the Bern Table of Call Signs. By this means alone it was possible to recognize and identify those messages after only a few minutes of listening.

Communications with an ally should be prepared with particular care and transmitted according to one's own radio system, and preferably with one's own personnel, in order to avoid all foreign characteristics. By way of summary, it can be stated that during the Norwegian Campaign British radio operators did not at all times observe the security measures which would have protected them from interception and evaluation by German intelligence.

The over-all results achieved by German radio intelligence during this campaign were quite modest and understandably so, in view of the shortage of equipment and personnel, which consisted of only one first lieutenant and twenty-four enlisted men. This is no way a reflection upon the quality of their work, however.

VII. Campaign in the West (1940)

(This section was written by Colonel Randewig, at that time commander of the intercept troops attached to Army Group A.)

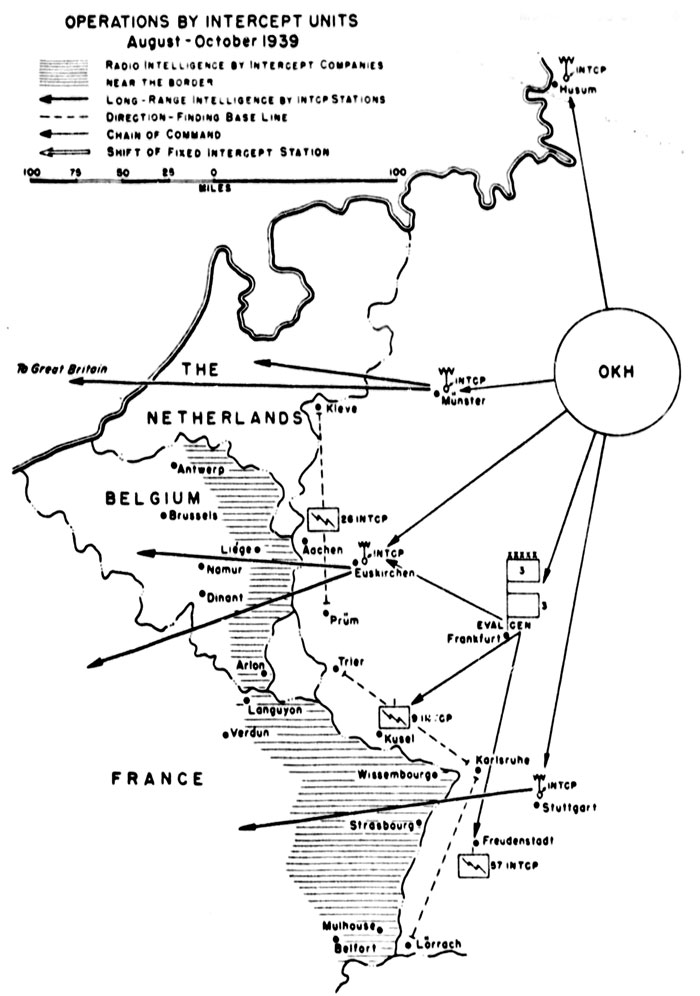

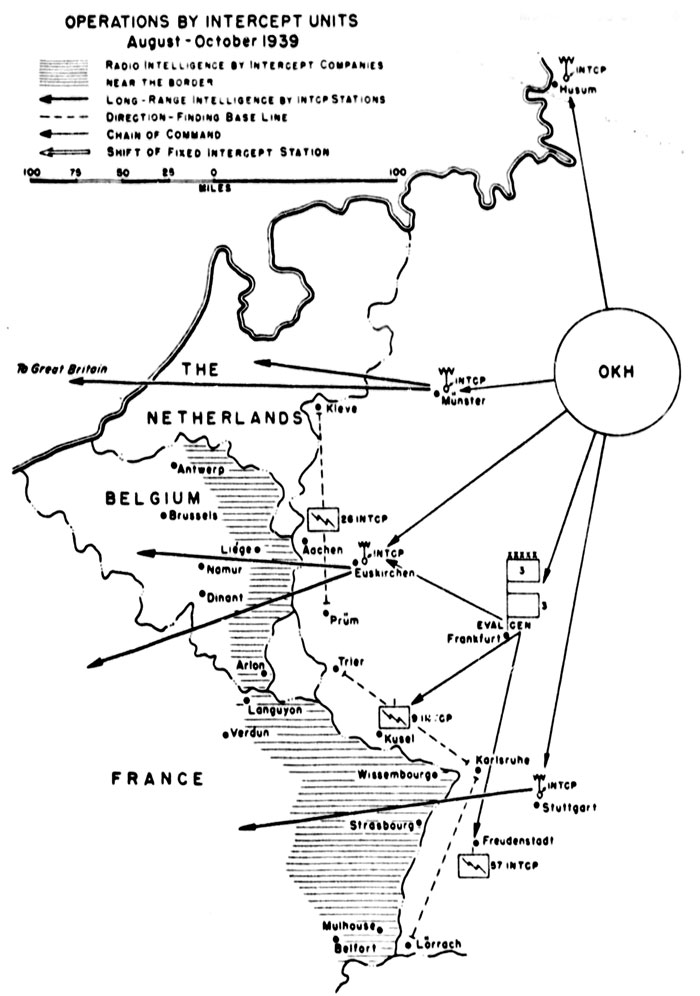

Prior to the beginning of the Western Campaign on 10 May I94O, the operations and command channel structure of German radio intelligence was divided into four chronological phases as illustrated in Charts 3 a-d.

GERMAN RADIO INTELLIGENCE

BY LIEUTENANT-GENERAL ALBERT PRAUN

Biographical Sketch of the Principal Author

Albert PRAUN was born 11 December 1894 in Bad Gastein, Austria. He entered the German Army in the 1st Bavarian Telegraph Battalion as an officer candidate in 1913 and served as battalion and division signal officer during World War I. He remained in the post-war Army and in 1939 was assigned to the Seventh Army on the Western Front as army signal officer. During World War II PRAUN served as regimental, brigade, and division commander, and also as army and army group signal officer in France and Russia. In 1944 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and simultaneously appointed Chief of Army and Armed Forces Signal Communications in which capacity he remained until the end of hostilities.

List of Other Contributors

(Last rank held and assignments relative to the present subject)

de Bary. Major, commander of radio intercept units.

Bode. Captain, intercept platoon leader: chief of the clearing center of Communication Intelligence West.

Gimmler. Major General, Chief Signal Officer under the Commander in Chief West and Chief of the Armed Forces Signal Communication Office. [Tr: Oberbefehlshaber, hereafter referred to as OB]

Gorzolla. Captain, liaison officer between the clearing center of communication intelligence and the Eastern Intelligence Branch.

Halder. Colonel, commander of intercept troops for an army group.

Henrici. Lieutenant colonel, General Staff, chief signal officer for C3 West.

Hepp. Colonel, General Staff, Deputy Chief of Army Signal Communication.

Karn. Colonel, army signal officer.

Kopp. Colonel, senior communication intelligence officer for OB West.

de Leliwa. Lieutenant colonel, chief of evaluation for OB West.

Marquardt. Major, liaison officer between the clearing center of communication intelligence and the Western Intelligence Branch, Army General Staff.

Mettig. Major, chief of the cryptoanalysis section of the main intercept station.

Muegge. Colonel, communication intelligence officer for an army group.

Foppe. Major, signal battalion commander.

Randewig. Colonel, commander of intercept units with various Army groups.

Seemueller. Lieutenant colonel, communication intelligence officer for several army groups.

Stang. Captain, radio company commander, armored divisions.

Chapter One. Introduction

Because of the difficulties encountered in this highly specialized field the topic required treatment by an expert of recognized standing. Since such an expert was not available among the men in the German Control Group working under the supervision of the Historical Division, SUCOM, the writing of the over-all report was assigned to General Praun. By virtue of the knowledge acquired by him in his military career, and especially during the tenure of his final position, General Praun has a thorough grasp of German radio intelligence. Moreover, as a result of his acquaintance with German signal service personnel, he was able to obtain the co-operation of the foremost experts in this field.

The German Control Group has exerted a guiding influence on the study by issuing oral and written instructions concerning the manner in which the subject was to be handled. Above all, it reserved to itself the right of final decision in the selection of the contributors and also retained control over the individual reports themselves.

With regard to the treatment of the topic assigned, General Praun, with the approval of the Control Group, decided to make his report in the form of a study in military history. Since no comprehensive records were available, he assembled the basic material for the various theaters of war and the most important campaigns by enlisting the aid of signal officers who had served in radio intelligence in the respective theaters. This material was supplemented by reports from officers who had hold important positions as experts in various branches of radio intelligence in the Array High Command and the Armed Forces (Wehrmacht) High Command [Tr: Oberkommando des Heeres, hereafter referred to as OKH; Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, hereafter referred to as OKW]. From the successes and failures of German radio intelligence General Praun has established criteria for appraising the enemy radio services. He is thus able to present an actual picture of the Allied radio services as seen from the German side during the war.

An attempt was made to include an account of all major American and British military operations against the German Army, and an appraisal of their use of radio communication. The material on Russia was treated in a different manner. Because of the vastness of the Russian theater of war and because the same observations concerning radio communication were made along the entire front, the results obtained by communication intelligence units serving with only one army group have been described. They are supplemented by accounts from other sectors of the Russian front.

In keeping with German practice since 1942, the term "communication intelligence" (Nachrichtenaufklaerung) has been used when units thus designated were assigned to observe enemy radio and wire communication, (The latter activity lost almost all importance as compared with the former.) Where the observation of enemy radio communication alone is discussed, the term "radio intelligence" (Funkaufklaerung) is used or — as was customary until 1942 — the term "intercept service" (Horchdienst).

Chapter Two. The Significance of Electronic Warfare

Toward the end of World War II about 12,000 signal troops of the German Army were engaged in intercepting the radio traffic of an increasingly powerful enemy. With the decline of the information gained by intelligence through aerial observation, prisoner of war interrogations, and reports from enemy agents, communication intelligence became increasingly important. In spite of the constant attempts of all enemies to improve radio communication and increase its security, German signal troops were able again and again to gain access to the information transmitted by this medium.

Thanks to communication intelligence, German commanders were better informed about the enemy and his intentions than in any previous war. This was one of the factors which gave the German command in the various campaigns of World War II a hitherto unattained degree of security. The fact that, during the final years of the war when the German Army Command was leading exhausted and decimated troops without reserves, it was able to offer less and less resistance to clearly recognized measures and intentions of the Allies, and that Hitler was unwilling to acknowledge the true situation on all fronts and the growing enemy superiority as reported in accurate detail by communication intelligence, is one of the deep tragedies of the German soldier.

Since wireless telegraphy and later wireless telephony were first used for military communication, there was no pause in the eventful contest between this important instrument of the German command (and subsequently also of troop units) on the one hand, and the corresponding facilities of the enemy on the other, as each side tried to profit from his knowledge of the other's communications as he prepared his countermeasures.

Following the first amazing successes scored by radio intelligence of a high-level nature in World War I, the quantity of information obtained, including that pertaining to tactical operations, increased so enormously with the amount of radio apparatus used by all the belligerent powers that large-sized "organizations had to be established for handling them.

The active radio services in all armies tried to insure the secrecy of their messages by technical improvements, by speed in operation, by chancing their procedure, by mere complicated cipher systems, by accuracy in making calls and replies and in transmitting other signals, all of which constituted "radio discipline." However, in opposition to these developments the enemy also improved his passive radio service, his technical equipment, his methods of receiving, direction finding, and cryptanalysis. The important part played in this contest by the proficiency of the technical personnel involved will be described later.

At the same time that this form of electronic warfare was being waged in World War II, there was another aspect which also gained steadily in importance, namely, the more technical high frequency war between opposing radar systems. This consisted of the use of microwaves for the location and recognition of enemy units in the air and on the sea, and the adoption of defensive measures against them, especially in air and submarine warfare.

For the sake of completeness there should also be mentioned the third aspect of electronic warfare, the "radio broadcasters' war* in which propaganda exports tried to influence any as well as other countries, by means of foreign language broadcasts over increasingly powerful transmitters.

All three aspects of this modern "cold war of the air waves" were carried on constantly even when the puns were silent. This study will be restricted to a description of the first aspect of electronic warfare.

Chapter Three. German Radio Intelligence Operations (1936 - 45)

In addition to the intelligence gained from interesting the routine radio traffic in peacetime and the occasional activity during maneuvers, the political and military events which preceded the outbreak of World War II offered abundant material because of the increased traffic between the nations concerned, the larger number of messages, and the refinements and deficiencies in communication systems which had hitherto not come to light. During this period the German communication intelligence organization and the specialists employed in it gathered a wealth of information. Without any lengthy experimentation they were later on able to solve the increasing number of new problems which resulted from the extension of the war.

I. Spanish Civil War (1936 - 39)

In the Spanish Civil War the supporting powers on both sides had opportunities to become acquainted with the radio systems, radio equipment, and cryptographic methods of their opponents. The German intercept company assisting Franco obtained much information on these subjects. Because of its successes this company was always assigned to the focus of the military operations.

II. Czechoslovakia (1938)

For a long time the entire radio net traffic of Czechoslovakia was easy to intercept and evaluate. It was observed by fixed listening posts and intercept companies in Silesia and Bavaria, subsequently also by stations in Austria. Toward the end of May 1938 one of the key radio stations in Prague, probably that of the War Ministry, suddenly transmitted a brief, unusual message which, in view of the existing political tension, was believed to be an order for mobilization. This message was immediately followed by changes in the radio traffic characterized by the use of new frequencies and call signs, and by the regrouping of radio nets which had been prepared for the event of mobilization. The result was that the intercept company then on duty was able within two and a half hours to report the mobilization of Czechoslovakia. During the next few days very primitive, simple radio nets appeared along the border and then disappeared again when the tension was relaxed, where-upon the entire radio net reassigned its original characteristics. Radio Intelligence was able to report that the mobilization order had presumably been revoked.

In the middle of September of the same year something incredible happened. The Czechs repeated what they had done in the spring. Again they announced the mobilization order by radio and within a few minutes the message was forwarded to Berlin. Again the same primitive radio nets appeared along the border with almost the same call signs and on the same frequencies.

This intercept operation was a practical object lesson, while the radio Service of the Czechs was a classical example of how not to carry en radio operations.

III. Polish Campaign

Polish radio communications were also well known, as the result of long observation, and were intercepted from points in Silesia and East Prussia. During the period of tension in the summer of 1939 the Germans observed not only the regular traffic but also a great number of field messages which increased daily and was far out of proportion to the known organization and radio equipment possessed by the Polish Army. As was soon conjectured and then later confirmed during hostilities, the purpose of this was to camouflage Polish radio communications by using three call signs and three frequencies for each station. Intelligence officers engaged in the evaluation of traffic and D/F data were unable to derive any detailed tactical picture from the intercepted messages. Nevertheless, the intercept service confirmed that the Polish assembly areas were located where the German General Staff had assumed them to be. It can no longer be determined whether the Poles employed these artifices for purposes of deception, as well as camouflage, in order to simulate stronger forces than they actually possessed. In any case, the failure to observe radio silence in the assembly areas was a grave mistake.

In 1939 the mobile facilities of the German intercept service were still inadequate. The intercept companies were insufficiently motorized and there was no close co-operation between them and the army group and army headquarters. The Polish radio communication system failed after the second day of the campaign, when it attempted to take the place of the wire lines destroyed by German air attacks. Probably as a result of the intercept successes they had scored in 1920, the Poles had restricted their peacetime radio activity to a minimum. As soon as they tried to carry out deception without previous practice in mobile operations, their radio communication collapsed completely. It was unable to keep pace with the rapid movements of the retreat, and moreover, the Poles were seized by the same type of radio panic that will be discussed later in the section of Allied invasion in Normandy. Clear-text messages revealed that many stations no longer dared to transmit at all, fearing they would he located by our direction finders and attacked from the air.

The Polish Army was thus unable to employ its radio communication for command purposes. Its leading source of information regarding the situation at the front were the OKW communiques, which, at that time, accurately reported every detail with typical German thoroughness. This mistake was corrected in the German campaign in the West in 1940. Intercept results were insignificant, since the Poles transmitted hardly any radio messages. The messages of some individual units were intercepted until there disbanded at the Galician-Romanian border. It was possible to solve several simple field ciphers even without trained cryptanalysts. Another mistake made by the Poles was the transmission of messages in the clear by the station of the Military Railway Transportation Office in Warsaw, which openly announced the time, route, and contents of railway shipments. These trains were successfully attacked by the Luftwaffe, which was further aided by other plain-text Polish traffic.

IV. USSR (1939 - 40)

After the conclusion of the Polish Campaign, the intercept company stationed in Galicia in the Sanok - Jaroslav - Sandomir area was charged with intercepting the traffic emanating from Russian units occupying eastern Poland. Thanks to their previous experience against Czechoslovakia and Poland, personnel of this company were so well trained that they rapidly became skilled in this new type of work. This company was not engaged in cryptanalysis. Solely on the basis of D/F reports and an evaluation of the procedure and traffic characteristics of the heavy traffic handled by the numerous stations, the Germans were able to deduce that a large number of troop units were in the area, but were at first incapable of ascertaining their organizational structure. All that could be determined was whether those units belonged to the army, the air force or to the NKVD [Tr: Comissariat of Internal Affairs, see TM 30-430, 1-26], whose radio operations were distinguished by a different technique from that used by the regular armed forces. For several months during the period of re-groupment everything was in a state of flux. The Soviet radio traffic was, however, well organized and efficiently handled.

Then the company intercepted messages from areas which were not actually assigned to it. When Soviet troops occupied the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and when they Subsequently attacked Finland, their short-wave transmissions from these areas were surprisingly well received in southern Galicia — even better than in areas further north. This was the discovery of great technical importance for the German intercept service. It could not have been arrived at by simple calculation since it resulted from physical conditions.

An abundance of messages, often in the clear, were received from the Baltic states and the Finnish theater of war, so that in the final stages of evaluation it was now possible to deduce the Soviet order of battle. In the case of units of division size and below their withdrawal from the Baltic States wan frequently ascertained on the basis of data including numbers, names of officers, and place names. Subsequently these elements turned up on the Finnish front in easily identified locations, from where they again disappeared after a while, only to reappear in the Baltic area or eastern Poland. Some vanished from observation altogether. From this fact it could be deduced that they had been transferred to the interior of the Soviet Union. Thus, the Germans could follow all movements of forces during the Russo-Finnish War simply by reading the intercept situation chart.

The radio communication of the Soviet Army in 1939 - 40 was efficient and secure under peacetime conditions, but in time of war, or under war-like conditions, it offered many weak spots to an enemy intercept service and was a source of excellent information for the German intelligence service.

V. German Campaign in the Balkans (I94I)

Since the results obtained from radio interception during the German campaign against Yugoslavia, Greece and the British Expeditionary Force are not of any special importance for an over-all appraisal of the subject, the campaign in the Balkans will be introduced at this point as one of the events preceding the beginning of major operations.

The German Army's organization for mobile warfare war still incomplete; results were jeopardized at first by the great distances between the intercept stations and the target areas, and later on by defective signal communication which delayed the work of evaluation. Intercept operations against the British will be described in detail in section VIII.

Chart 1. Operations of Communication Intelligence Units Against the Balkans and the Near East, February 1941

The Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast, whose headquarters is indicated in Chart 1 as being that of a regiment, was responsible to Field Marshal List, the Twelfth Army Commander. He was in charge of the two fixed intercept stations In Graz and Tulln (near Vienna) and two intercept companies. His sphere of action comprised the entire Balkan Peninsula, Turkey, and the British forces in Greece and the Middie East.

Until late 1940 radio interception against Greece and the Near East was carried out only as a secondary task and with inefficient resources by the Tulln station. The great distances, for instance 780 miles between Vienna and Athens and 1,440 miles between Vienna and Jerusalem, were a significant factor. (For purposes of comparison with intercept operations in the West it might be mentioned that the distance between Muenster and London is only 312 miles.) The value of the results was in inverse proportion to the distance involved.

In the beginning of 1941, when it was planned to enlarge the intercept service against Greece, especially after the landing of the British forces, the above-mentioned units, except for the Graz station, were transferred to Romania. In February 1941 the Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast and his evaluation center were stationed in Bucharest. From a location near this city the "Tulln station" covered Greece, giving its main attention to British communications emanating from there and the Middle East. One of the intercept companies also located in the vicinity of Bucharest observed Yugoslavia in addition to British radio traffic in Greece. The other intercept company in Bacau (150 miles northeast of Bucharest) had to carry out intercept operations against Soviet Russia and the Romanian police, whereas the Graz station, whose main attention was directed at Yugoslavia and Italy, intercepted traffic of the Romanian and Hungarian police. (See Chart 1).

Before the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans the Germans detected Greek army units in the northeastern corner of the country, Royal Air Force operations around Patras and between Patras and Athens, and British ground forces in Cyrenaica. They also intercepted messages from British border troops in Transjordan.

After the entry of German troops into Bulgaria the above-mentioned units (except the Graz station) were transferred to that country, and the intercept company in Bacau also covered Greece. The results were similar to those formerly obtained. It was not yet possible, however, to break the Greek ciphers because of an insufficient number of intercepted messages, and the German units had to be content with traffic analysis. On the other hand, it was possible to break the British field cipher in Palestine.

Following the attack upon Greece on 6 April brisk radio traffic was intercepted and evaluated. The disposition of the Greek forces in northern Greece was revealed and could be traced. West of the Vardar in the British Expeditionary Force sector, our intercept units detected three radio nets comprising fourteen stations, representing an armored unit northeast of Veria which was subsequently transferred to the area south of Vevi, a British division north of Katerini, and another division west of Demetrios. It was confirmed that these forces had remained for several days in the areas reported. On 8 April, the following British message in clear text was repeatedly heard: "DEV reporting from LIJA — Strumica fallen, prepare immediate return!"

In the Near East we followed the movement of a British regiment from Palestine to Egypt. The first indication of this was the message of a paymaster in the British military Government ordering a certain agency to be particularly careful to prevent the departing regiment from taking any filing cabinets along with it, since they were needed by the military government office. Thereafter, the recipient's movements could be clearly traced.

Radio intelligence against Yugoslavia produced an excellent picture of enemy positions. Three Armeegruppen [Tr: a weak improvised army under an army commander with an improvised army staff] and one corps from each were located near Nish, Ueskueb and Stip, and later one at Veles.

Very little radio traffic was heard in Turkey. By the middle of April German radio intelligence located Greek troop units between the Aliakmon River and the Albanian border, and also followed the witndrawal of a British armored unit from the vicinity of Vevi to the Kozani area, subsequently to Eleftochorion, and thence to Trikkala. The withdrawal of both British divisions (Anzac Corps) and, a few days later, further withdrawals to the area of Larisa were observed.

In the middle of April the Commander of Intercept Troops Southeast moved to the Salonika area with the "Tulln station," elements of the Graz station, and one intercept company. The other intercept company was released for service in Russia.

Greek radio traffic diminished rapidly and ended with the capitulation on 21 April. German intercept units continued to follow the traffic of the British Expeditionary Force until it disappeared from the air after the final embarkation in late April. The intercepting of British traffic from Crete and the Aegean islands was continued. During subsequent British operations in the Dodecanese Islands, for instance the occupation of Rhodes, the enemy often transmitted important situation reports in the clear.

VI. Norway and Denmark (1940)

The mobile operation of an intercept platoon in the Norwegian Campaign in I940 suffered from all the defects inherent in inadequately prepared improvised operations. A few radio operators were picked from each of six different units in the West, but no translators or cryptanalysts. The equipment was also inadequate. Later on, there was no shipping space to move the platoon up. In time and close enough to the German operations staff and the enemy area which war to be covered, nor was the platoon given any data or instructions.

In its first operation, which was carried out with the assistance of the Husum Fixed Intercept Station, the platoon intercepted only coastal defense messages in clear text from Denmark concerning ship movements. No army radio traffic was heard. Even these messages ceased on 9 April. Because of the great distance only a few Norwegian coastal stations were heard. Up to 8 April this traffic was normal, but on the night of 8 - 9 April it increased to a point of wild confusion. Normal army radio traffic was observed in Sweden. After the platoon's first move to Als on the Kattegat, Norwegian Army messages were also intercepted, as well as traffic between Swedish and Norwegian radio stations. It was not until 24 April, that is, eleven days after the operations had commenced, that the intercept platoon was moved up to Oslo and thus employed in the vicinity of the German operations staff. (Chart 2)

Chart 2. Radio Intelligence During the Norwegian Campaign, 31 March - 14 June 1940

The Norwegian Army stations usually transmitted in the clear. Radio stations in central and southern Norway were intercepted, but few of the massages were of any tactical value.

Radio messages between Great Britain and Norway were more important. The admiralty station transmitted encrypted orders to the naval officers in command of Harstadt, Andalsnes, and Alesund. Although these messages could not be solved, they provided clues to the most important debarkation ports of the British Expeditionary Force. In particular, they confirmed the landings near Harstadt, which had hitherto been merely a matter of conjecture.

The Germans intercepted the field messages of the British units which were advancing from the Andalsnes area by way of Dombas - Otta - Hamar to Lillehammer in the direction of Oslo. They used code names for their call signs and signatures. The messages themselves could not be solved. However, since the code names ware learned after a short time from captured documents, the chain of command and composition of units were soon clearly recognized and the enemy's movements were followed.

Swedish radio stations were frequently heard transmitting to Norwegian stations. They handled mostly official and business messages. Norwegian radiograms were then often relayed from Sweden to Great Britain.

When, in the middle of May, a part of the German command staff was transferred to Trondheim the intercept platoon went along and found especially favorable receiving conditions near this city, which is approximately 1,500 feet above sea level. A large Norwegian radio net regularly transmitted air reconnaissance reports, information on the composition and commitment of the Norwegian 7th Division, and mobilization orders for the unoccupied part of Norway. They mentioned General Fleischer as commander in northern Norway.

Two radio stations continued to operate east of the island of Vega in the rear of the German 2d Mountain Division, which was advancing to relieve Narvik, until they were knocked out as the result of intercepts. The majority of the radio stations which were observed were in the Narvik area or north of it. The Alta ski battalion was often mentioned as being in action. Additional stations of other radio nets were identified in Kirkenes, Vardo, Harstadt, Tromse and Honningsvag, After the end of hostilities on 9 June all Norwegian radio traffic stopped within a few hours. Messages from British and French units were also picked up, as well as the traffic of the Polish mountain units. For the purpose of avoiding confusion with internal French traffic, a temporary teletype line to the commandor of the German intercept troops in France was set up, so that any sky waves from France could be recognized and timed out.

In order to furnish Kampfgruppe [Tr: a term loosely assigned to improvised combat units of various sizes, named usually after their commanders] Dietl in Narvik with radio inteligence of purely local importance without any loss of time, the intercept platoon was ordered to organize a short-range intelligence section, but as a result of the development of the situation this section never saw action. Instead, intercepts of interest to Kampfgruppe Dietl were forwarded to it through Sweden by telephone and teletype. During 7 and 8 June all non-Norwegian radio traffic stopped. In this way the withdrawal of the Allies from Narvik wan confirmed. This was also reported to Kampfgruppe Dietl.

The traffic between Great Britain and Norway, which had already been intercepted near Oslo, was now observed in larger volume from Trondheim. Most of the traffic was between Scotland (possibly Prestwick) and Bode or Tromse. The volume of messages was very large. The average word count was 200 letters. Every evening the Germans intercepted situation reports of the Norwegian High Command in Tromse, orders from the Admiralty in London, mine warnings, SOS calls, government radiograms to England and France, personal messages from King Haakon to King George of England and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and reports from the Reuter correspondents attached to Norwegian units.

On 25 May the radio station in Bode was destroyed by German bombers. Scotland called Bode for twelve hours in vain. Messages then transmitted by the Vadso Station were immediately intercepted. The Germans continued to intercept the traffic between Norway, Sweden and Great Britain.

Both the Trondheim station and the intercept platoon radioed a demand for surrender to the Norwegian High Command in Tromse. After its acceptance these radio channels were kept in operation until the middle of June when the platoon was disbanded and its personnel returned to their former units on the Western Front.

British radio traffic was, as usual, well disciplined and offered few opportunities to German radio intelligence. For this reason the intercept platoon endeavored to work on as broad a scale as possible, to intercept a large number of messages, and to probe for soft spots. Since it lacked special equipment and suitable personnel, the British ciphers could not be solved. Therefore, clear-text messages or code names and traffic analysis had to suffice as source material. The evaluation, therefore, was based chiefly on the procedural aspects of enemy radio operations.

Today it appears incomprehensible why the British seriously impaired the value of their well-disciplined radio organization and their excellent ciphers by transmitting call signs and signatures in the clear. Operating mistakes of this kind provided valuable information to the German intercept service, although it was poorly trained and insufficiently prepared. Subsequent experience on other battlefields showed that more extensive and intelligent efforts on the German side would have resulted in even more opportunities for breaking British ciphers.

British-Norwegian radio traffic was typical of the deficiencies which develop in a coalition with a weaker ally. It was carried on according to Norwegian standards and offered a wealth of information to German communication intelligence. The British and Norwegians were apparently unable to use a common cipher. On the other hand, the operating efficiency of their radio communication was high. The Norwegian personnel appeared to have been recruited from the ranks of professional radio operators.

At this point it should be repeated that the use of clear-text messages and code names should be avoided as a matter of principle. If code names were considered indispensable, they should have been frequently changed. A decisive transmission error prominent in traffic between the British Isles and Norway was the use of call signs in the clear as listed in the Bern Table of Call Signs. By this means alone it was possible to recognize and identify those messages after only a few minutes of listening.

Communications with an ally should be prepared with particular care and transmitted according to one's own radio system, and preferably with one's own personnel, in order to avoid all foreign characteristics. By way of summary, it can be stated that during the Norwegian Campaign British radio operators did not at all times observe the security measures which would have protected them from interception and evaluation by German intelligence.

The over-all results achieved by German radio intelligence during this campaign were quite modest and understandably so, in view of the shortage of equipment and personnel, which consisted of only one first lieutenant and twenty-four enlisted men. This is no way a reflection upon the quality of their work, however.

VII. Campaign in the West (1940)

(This section was written by Colonel Randewig, at that time commander of the intercept troops attached to Army Group A.)

Prior to the beginning of the Western Campaign on 10 May I94O, the operations and command channel structure of German radio intelligence was divided into four chronological phases as illustrated in Charts 3 a-d.